Image: House by CEPAR Associate Investigator Dr Katja Hanewald, Senior Lecturer in the School of Risk and Actuarial Studies at UNSW Business School and Director of Research for the Ageing Asia Research Hub as part of CEPAR, Tin Long Ho, CEPAR Ph.D. candidate at UNSW Sydney, and Robert Eaton, principal at Milliman. This article is republished from BusinessThink. Read the original article.

Individuals and society as a whole face a range of challenges around how to fund long-term care. Most individuals will need long-term care at some point as they get older. The US Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) estimated that 47 per cent of US men and 58 per cent of US women who recently turned 65 will need some form of long-term care over the rest of their lives and that they will need this care for 1.5 to 2.5 years on average. The median annual cost of this care estimated by Genworth in 2019 ranged from about $50,000 for home health aides to over $100,000 for private nursing home facility rooms.

The HHS estimates that those people who will need long-term care will finance 53 per cent of their needs out-of-pocket, with private long-term care insurance picking up only 3 per cent of the total share (Medicaid accounts for much of the rest of this spending). This is a tall order for most people given that very few can afford to fund formal long-term care needs from their savings.

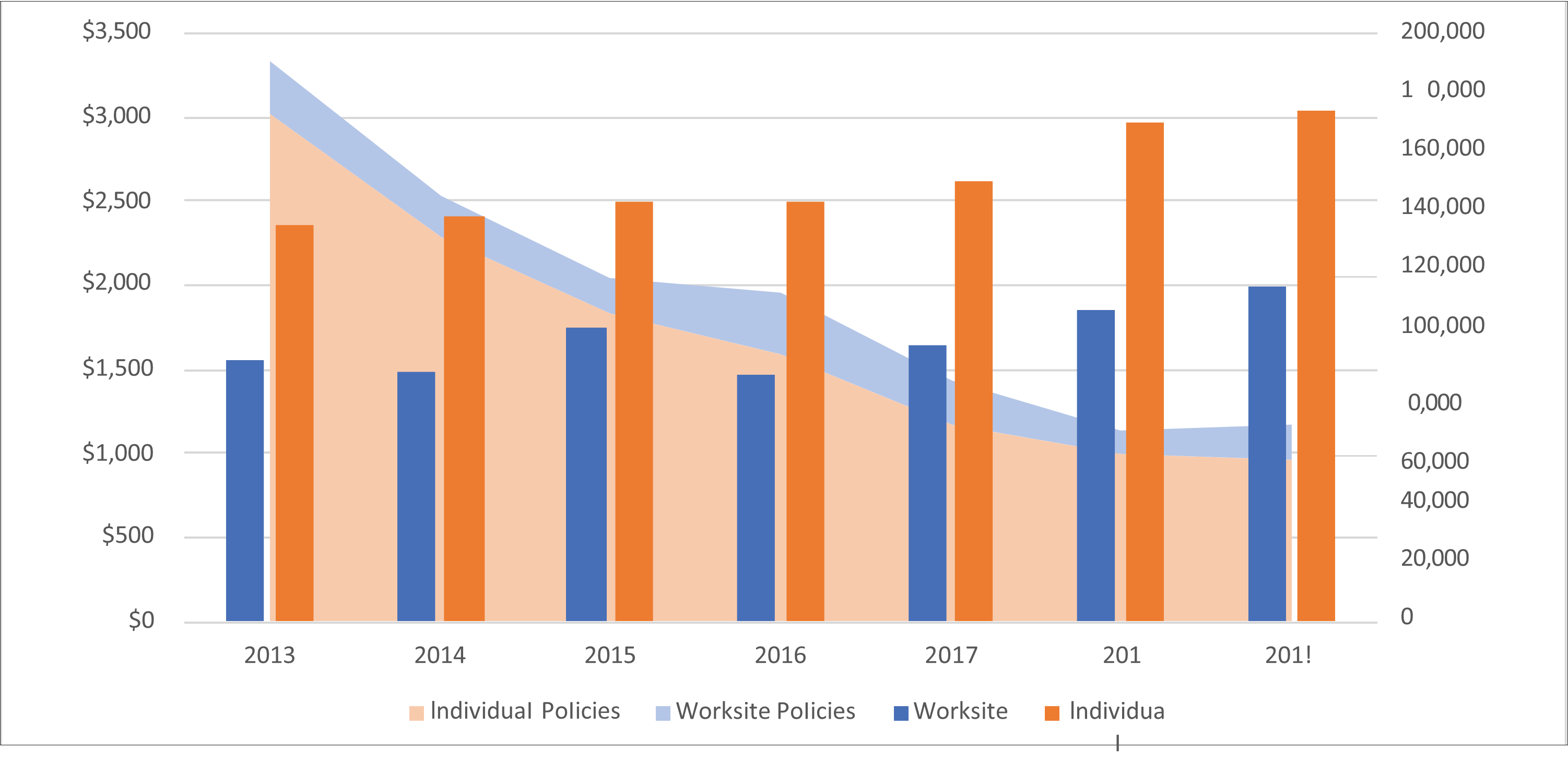

The traditional private long-term care insurance market in the US provides comprehensive coverage for those individuals who can afford it, and who are healthy enough to pass underwriting, but the policies can be expensive. The below chart shows the average premium and count of insureds who have purchased traditional long-term care policies in the individual and worksite markets from 2013 to 2019. Sales of long-term care insurance have been decreasing steadily over this time period (16 per cent per year on average), while premium rates for new sales have increased nationwide about 3.9 per cent per year over this period.

US long-term care insurance new sales average premiums and policy counts

Source: LIMRA Individual Long-Term Care Insurance annual report, Broker World Analysis of Worksite long-term care insurance survey

At the same time, many older individuals own their homes. They often have an emotional attachment to their home and prefer to stay in their home for as long as possible as they age. Housing wealth is not just emotionally valuable, it also often forms the largest part of individuals’ total wealth. However, housing wealth is an illiquid type of asset. In order to access the accumulated savings in the family home, individuals typically have to sell and move, which they are reluctant to do.

There are new approaches to long-term care financing that rely on home equity release which address several of the challenges mentioned above. While these approaches could help expand the potential for long-term care financing to middle-class Americans, even these approaches don’t address a large swath of the US with less privilege, who have little or no home equity. There are product design, marketing, pricing, risk management and potential behavioural factors that should be considered in the process.

Product description

Housing wealth may be used to fund long-term care. There are two components in the transaction: how housing wealth is unlocked and how it is used to finance long-term care. These components can be combined in different ways. And while unlocking and financing can be found in the US and other markets internationally, a combined product has not yet been introduced.

Unlocking housing wealth

The easiest way to fund long-term care using housing wealth is to sell the property and use the sale proceeds to either cover long-term care insurance premiums or long-term care costs as they arise. There are many reasons why most people don’t do so. Most house sales mean that people are moving unless a sale-and-leaseback is possible. People moving also incur sales taxes and moving costs. The strategy to sell to cover long-term care costs is particularly challenging for couples or families with only one person in need of care: the other family members still need a place to live, and they prefer to remain in the family home. Because most people won’t sell their home to finance long-term care, we look to home equity release products that allow individuals to access their housing wealth while still living in the home.

The most common form of home equity release are reverse mortgages (also called “lifetime mortgages” in the UK). Reverse mortgages are loans that allow individuals to borrow against their home equity without having to make capital or interest repayments while they live in their homes. Individuals can typically choose to receive the payouts as a lump sum, an income stream or a line of credit. All payouts that the individual receives become a debt that accumulates interests. Fees and mortgage insurance premiums are also charged against the loan account. The outstanding debt is settled when the borrower permanently moves out of the home, either because they permanently enter a nursing home or because they have passed away. In either case, the home is sold, and the sale proceeds are used to settle the outstanding debt.

Reverse mortgages typically feature two important guarantees: a guaranteed right of the individual to stay in their home (“lifetime occupancy”), and a no-negative equity guarantee, which ensures that only the sale proceeds are used to settle the outstanding debt. The no-negative equity guarantee protects the borrower and their estate from having to provide additional resources to cover the debt. With a reverse mortgage, homeowners choose the amount they wish to borrow and receive as payouts, subject to maximum loan-to-value ratios set by the provider. The level of payout for a given loan amount depends on the characteristics of the property and the age of the borrower.

Another form of home equity release is called home reversion. A home reversion contract involves a partial sale and leaseback of the individual’s home. The homeowner chooses a percentage of their current home value that they wish to sell. The payout they receive reflects the current market value of the property share minus fees and minus the present value of the lease-for-life arrangement that is part of the contract. This value of the lease-for-life arrangement is subtracted because the individual is renting back the part of the property that they sold to the provider. At the end of the contract, the home is sold and the sale proceeds are shared based on ownership proportions. Home reversion contracts are available in several markets, including the U.K. and Australia.

Reverse mortgages and home reversion plans are the most common types of home equity release. Other forms of home equity release include:

- Viager: A real estate transaction, popular in France; a contract between two private parties, where the buyer makes a down payment and then a series of payments for as long as the seller is alive.

- Shared appreciation mortgages: The consumer shares a percentage of the appreciation in the home’s value with the lender in return for paying reduced or no interest on that part of his or her borrowings.

- Home income plans: The equity released through a reverse mortgage or a home reversion plan is automatically invested into an annuity that generates income for life.

Home equity release arrangements usually terminate when the homeowner dies or permanently moves into a nursing home. Let’s look at how these arrangements can be used to fund long-term care, both at home and in a nursing home.

Financing long-term care with housing wealth

A simple way is to use the home as an “ATM” (or “equity bank”) and withdraw cash as needed to cover formal costs of long-term care. One advantage of this strategy is that if the individual never incurs long-term care costs, the value of the home is preserved and can be used for other purposes, including a bequest. A disadvantage of this strategy is that it does not provide insurance through risk pooling. The individual can face very high out-of-pocket long-term care costs, which could exceed the home value.

Alternatively, the additional liquid wealth obtained via home equity release can be used to purchase long-term care insurance. Home equity release contracts such as reverse mortgages and home reversion plans can fund a single upfront premium or a regular monthly or annual premium. Higher upfront premiums will deplete home equity faster. The insurance benefits can reimburse long-term care costs, or indemnify the policyholder depending on their care needs.

Furthermore, home equity release can fund the deposit or bond required for an individual to enter a nursing home or retirement community (such as a continuing care retirement community, a CCRC). This arrangement is especially useful for couples or families living together when only one person needs care while other family members still require a place to reside and prefer to remain in the family home.

Most individuals prefer to remain in their homes as they age and receive informal care from a family member. Financing long term care through a home equity release can address both these needs by allowing individuals to access the accumulated savings in their home while still living in the home, and by providing the resources to pay an income to an informal care provider.

Product design and marketing

Two critical factors to consider in developing such products are design and communication. Home equity release products (reverse mortgages, home reversion) and long-term care insurance are complex products in themselves, and their combination can be challenging to understand. Product understanding is a key driver of the demand for retirement financial products such as reverse mortgages.

Providers must design products that potential clients can understand. We have analysed home equity release products offered in different markets, including Australia and China, and found that some products are unnecessarily complex. For example, one reverse mortgage product piloted in China provides fixed monthly payments for life, which are partly structured as a deferred annuity. While this structure might be attractive from the insurer’s perspective, it is difficult to communicate to potential customers, and this was one of the reasons this product failed to attract demand.

The demand for equity release products is higher when customer needs and concerns are openly addressed. For example, potential customers are sometimes concerned that they may be evicted from their property. To address this concern, providers emphasise the guaranteed lifetime occupancy. Potential customers may also view reverse mortgages as unattractive when house prices are increasing. Fortunately, in a reverse mortgage, homeowners and their estate participate in house price increases and are protected against downturns in the housing market by the no-negative equity guarantee. With a home reversion arrangement, homeowners remain exposed to house price fluctuations for the fraction of housing wealth they retain.

Providers should openly address bequest motives and intergenerational transfers. Based on our research, long-term care strategies described here should be marketed to older homeowners and their adult children as both groups sometimes have misconceptions about each other’s views on housing wealth. In one study we conducted in China, some older homeowners rejected the reverse mortgage because they wanted to leave their property to children or grandchildren, while very few of the adult children we surveyed were concerned about this. At the same time, a number of adult children thought their parents would not be interested, even though reverse mortgage approval rates were high among older homeowners. Companies selling these products can emphasise that long-term care financing strategies based on home equity release can reduce the burden on children and grandchildren, who might have debt and low incomes themselves, and can provide resources to facilitate informal care. The product design can also include an option for children to settle any outstanding reverse mortgage debt or buy back the home reversion share, and keep the property within the family.

Finally, there is a perception that older homeowners are an especially vulnerable group of customers. However, many older homeowners have decades of experience in dealing with mortgage lenders because they had traditional (forward) mortgage loans during their working lives. Mortgage borrowing is also increasing among older Americans: Between 1980 and 2015, mortgage usage by homeowners 65 and older increased from 13 per cent to 38 per cent. Some customers might be reluctant to take on debt again after having paid off their mortgage over many years. To address this concern of debt aversion, product messages may highlight how long-time homeowners deserve to access the value in their homes – which they have earned over years of payments – in a time of long-term care need.

Pricing and risk management

Strategies and products that combine the use of housing wealth to fund long-term care are exciting and novel areas of research. These products may provide an attractive solution to the challenge of how to fund long-term care by allowing individuals to use their housing wealth. These strategies and products are also interesting from a modeling perspective, as they require estimating uncertain factors and risks.

For example, reverse mortgages typically include a no-negative equity guarantee, which caps the borrower’s repayment at the house price at the time of termination. Pricing this guarantee is central to the pricing and risk management of reverse mortgages. This pricing exercise requires projections of house price growth rates and interest rates over a long time-horizon. House price growth varies substantially across suburbs and depends critically on the property’s characteristics, including location. The properties of older homeowners often have different characteristics than new properties (such as the kitchen layout and the number of bathrooms) and are maintained differently as the homeowner ages. Ideally, such factors should be considered when estimating future home value. In our research, we have used vector autoregressive with exogenous variable (VARX) models to project disaggregate house price indices rates along with other macroeconomic variables.

For home reversion, a lease for life agreement is usually embedded in the contract. After selling part of the property, the occupants actually need to pay rent for the proportion they sold. The lease for life agreement represents the rent of the proportion of the home that is sold. Therefore, the proceeds of the home reversion consist of two components: a lease for life agreement, and the purchase of long-term care insurance. To calculate the value of the lease for life agreement, on top of the components mentioned in reverse mortgage considerations, the rental yield also needs to be considered. In addition, the expected calculation of the lease for life value should also include the likelihood that the occupant moves out, as well as mortality and the incidence of requiring long-term care services outside the home.

Pricing the new strategies and products also requires modeling the borrower’s life expectancy and their chance of needing long-term care. Today’s state of the art for such modeling is a first-principles, multi-state transition model, following an individual’s transition in and out of long-term care states, into potential lapsation, and death. If the product provides reimbursement-based payments, the pricing will model inflation in the cost of long-term care. Products that are sold to couples need to account for joint disability and survival rates.

Pricing these products can be effective using stochastic models that capture the correlation in assumptions over the time horizon. Stochastic models allow the pricing team to vary key, interrelated assumptions such as reimbursement costs, home prices, underlying economic factors, asset returns, and even geographic migration. The complexity of these products will require expertise drawn from many areas of actuarial, insurance, and finance practice, and an elevated degree of collaboration.

Another factor to consider is the payout structure from the equity release product. Reverse mortgages that pay out a high lump sum at the beginning of the contract are riskier from a provider’s perspective than those that pay out smaller amounts over time: The outstanding debt typically accumulates faster due to compound interest than the home value. One risk management strategy to address this is to offer loan-to-value ratios that start low for younger borrowers and increase by age. However, this strategy might suppress demand.

There can be interesting selection effects in products that combine home equity release and long-term care insurance. For example, reverse mortgages are attractive for long-lived individuals as there are no repayments while the individual is alive. If these long-lived people are also healthier, a combined reverse mortgage/long-term care insurance product may face less adverse selection than standalone long-term care insurance.

Dr Katja Hanewald is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Risk and Actuarial Studies at UNSW Business School and Director of Research for the Ageing Asia Research Hub as part of CEPAR. Co-authors include Robert Eaton, principal at Milliman, and Tin Long Ho, a Ph.D. candidate at UNSW Sydney. For more information, please contact Dr Katja Hanewald directly. A version of this article appeared in the November 2020 issue of Long-Term Care News, published by the Long Term Care Insurance Section of the Society of Actuaries.